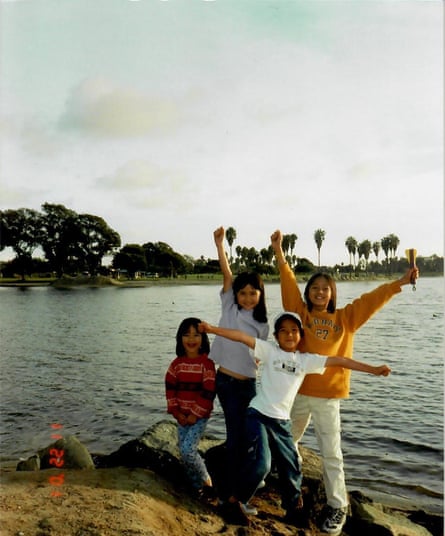

My family’s first home in the US was a two-bedroom suite at the Budget Inn La Puente in Los Angeles’ Walnut Valley. Every morning, my three siblings and I would jump on the sickly green bedspreads, chug Tropicana from the mini fridge and dash out the door. We’d play in the hallway or scamper out to the sun-baked sidewalks to marvel at the passing American cars. When police sirens blared down Francisquito Avenue, mom and dad would run outside, frantically waving us back in.

My parents had little choice but to stay at this motel because it was at a walking distance from our church, a largely Thai congregation for which my dad had moved from Malaysia to help run. We depended on the church for rides to the bank, advice on which car dealerships sold to immigrants and so much more.

That’s because my parents couldn’t open a bank account, buy a cell phone, buy a van or rent an apartment without great difficulty. It wasn’t due to a lack of funds. Although my dad’s vocation was as a pastor, during the daytime he worked as an engineer. The Los Angeles firm that hired him sponsored his H-1B visa, gave him benefits and paid him decently. My parents both spoke fluent English, held bachelors degrees from the UK and Australia and arrived on US soil with $20,000.

But these advantages amounted to little because their Fair Isaac Corporation (Fico) credit score was a big, fat zero.

A Fico score is your financial report card, and a prerequisite for any financial future in the US – from renting an apartment to buying a car or starting a bank account. Your Fico score, calculated by credit agencies and regulated by the US government, tells lenders if you can be reliably trusted to pay your bills. New immigrants must navigate a convoluted path to secure one.

The score only pulls credit history from the US, creating a huge barrier for new immigrants trying to establish stable lives. The credit history my parents built for more than two decades in Malaysia – through credit cards, home ownership and paying off their car – amounted to nothing here.

Thus ensued a chicken-or-egg conundrum. To build a score, my parents needed to create a reliable history of US-based payments – mortgages, retail instalments, credit cards – but institutions wouldn’t trust them with these financial obligations without an established score.

It’s no wonder that nearly 36% of foreign-born noncitizens do not use mainstream credit, compared with only 18.5% of the US-born population, according to a 2017 FDIC national survey. The agency also reports that about 51% of foreign-born noncitizens are either unbanked or underbanked.

My family came here with resources and a head start, but for people with less income, less English fluency or no documentation, it can be even harder to access mainstream financial institutions. It forces many new immigrants to rely on their informal networks to meet basic needs such as housing, getting a car and cell phone service.

‘I was a professional, but they didn’t treat me like one’

My parents’ quest to build up their credit began in bank lobbies. They dragged our family of six from bank to bank, facing a string of rejections. They finally found a Washington Mutual branch that let them open an account without a credit score. Still, we spent hours languishing in that sparsely furnished lobby, waiting as my dad tried to convince the bank specialist to issue him a credit card. I remember watching my dad sit behind a glass door, shaking his head in confusion. He presented pay stubs from his job as an engineer. All they would allow was a prepaid card.

To this day, the indignity of that experience rankles my father. “It was very frustrating to be treated this way,” he told me on a recent call, his voice rising. “I was a professional, but they didn’t treat me like one.”

My dad finally found a credit card company that would recognize his credit history from abroad – American Express – but for everything else, like other immigrants, we relied on our local networks.

Studies have shown how immigrant networks serve as a powerful mechanism for the newly arrived to find jobs and start businesses in the US. Many turn to informal lending circles within their communities in order to borrow or save money, turned off by mainstream banks’ high fees, minimum balances and requirements for Social Security numbers. My parents didn’t participate in these circles, but they leaned on their own immigrant network: the church.

During our first week, my parents complained to their church friends about how no company would sell them a phone plan because of their lack of credit history. One friend asked her brother-in-law, who ran a successful Thai restaurant in El Monterey, to co-sign the phone plan as a guarantor. The next week, the pastor of our church heard we were looking for a car. Without a credit score, he told us, it would be impossible to get a bank loan for our car purchase. But he had a solution. During the week, he worked as a Nissan mechanic. He knew a Nissan car dealer run by Koreans with connections to a Korean bank – they would give my dad a loan based on his paystubs. After a few weeks of staying in that motel, my parents met a sympathetic woman in church who offered to take us into her suburban family’s home. It wasn’t a lot of space for the six of us, but we were able to save money on rent.

But my parents quickly learned the risks of relying on small immigrant networks; some people took advantage of our desperation, while others gave charitably but with strict conditions. The bank that gave us the car loan charged predatory interest rates: 20%, while the average car loan rate that year was several percentage points lower. The woman who took us in grew frustrated with our family after several days. The toll of ten people – two families in a total – living in a three-bedroom house was too much to bear after a few weeks.

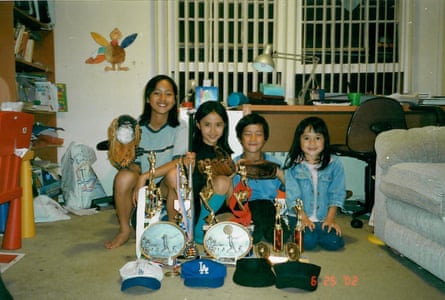

My parents began looking for apartments with renewed urgency, but after one look at our credit score, every landlord declined to rent to us. Then, a Taiwanese landlord accepted our application. My parents sighed with relief when they got a call from their broker; we celebrated by treating ourselves to Jack in the Box that night before driving to Ikea. Mom and Dad were annoyed but shrugged it off when they discovered that the “third bedroom” advertised was really just an off-shoot from the living room separated by a swinging door. All four of us kids slept in that room with mattresses on the floor; it was great fun for us. When we left several months later, my mom made sure to vacuum every inch of the apartment and pick up every piece of trash. But our landlord kept our entire security deposit anyway.

From ‘credit invisible’ to ‘credit worthy’

Our immigrant networks were helpful but only to a point. We needed a more systemic intervention, one that would turn my parents from “credit invisible” – those whose financial histories are not counted in the calculation of a Fico score – to credit worthy. We needed an expansion in how the score is calculated.

The Fico score is mostly determined by three private agencies: Experian, Equifax and TransUnion. If the Fico score is the default method by which landlords, banks and store-owners determine who is trustworthy, the score aught to include more data-points – such as a person’s on-time rent payments, income, cashflow and savings – than what is now considered.

There are signs of change. Dozens of startups have now pioneered alternative models to assess credit-worthiness and are working with the CFPB. In the fall of 2020, California passed a first-in-the-nation law mandating that landlords of subsidized housing report rent payments to credit agencies, creating credit-building opportunities for low-income tenants. Typically, only mortgage payments are reported.

Non-profits and community development credit unions continue to provide safe “credit-building” loans. They often serve low-income immigrants who don’t speak English fluently and may lack documentation. But the credit unions’ modest assets – billions shy of their big bank competitors – limit their reach.

One solution to expand the reach of credit unions would be a public bank. Deyanira Del Rio, board chairperson of the Lower East Side Federal Credit Union in New York City, advocates with the New Economy Project for city government to hold its $90bn in annual funds in a “public bank”. It would partner with community development credit unions, instead of stashing the funds in private banks to profit from.

Expanding our financial and credit system helps everyone, especially low-income immigrants without documentation, degrees or fluency in English. This incentivizes people to move their informal financial activity officially “on to the books” so they may build a formal track record recognized by credit agencies and build more stable lives.

After several stressful months, my parents eventually found their footing in the financial system. My dad emerged from that harrowing process with an aphorism he would repeat to us kids: “Don’t let anyone push you around: stand up for yourself.” This is the lesson he’s taken away from our transition to the US: fight for what you need.

But I would rather live in a country where newcomers don’t need to fight so hard for something so basic. Until we do so, many immigrants will continue to live precariously in motels and spare rooms, and borrow and spend in the shadows.

This piece was supported by the journalism non-profit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Kai Ngu is a writer and MA student at Yale Divinity School. Born in Borneo, Malaysia, they are most recently from New York City where their six-person family resides. As a journalist, they have written for publications such as the Guardian, Vice, Vox and Asian American Writers Workshop. Follow Kai (@kailinngu) and read their writing at kailinngu.com.