“It was the blood and flesh of contemporary art that really got my interest,” says Uli Sigg, Swiss businessman, former ambassador to China and North Korea, and reputed to be the largest private collector of contemporary Chinese art in the world. In 2012 he gave 1,463 works from that collection to Hong Kong’s M+ museum, valued at $163mn, and sold them another 47 for $23mm. He owns another 900 works of art and is still acquiring.

He is talking to me from his 17th-century Mauensee castle, which sits on a private island on Mauensee lake, near Lucerne in Switzerland. Sigg, 77, is sitting in a wood-panelled room, wearing an open-necked check shirt. His grey hair is cropped short and there is something of a bird of prey about him, but also joviality and friendliness. Behind him is a series of coloured canvasses, each with text.

“They carry slogans used by banks before the global financial crisis, they were used in advertising, even in the Financial Times!” (“Times are changing; we’re ready,” says one.) The works are parodies by the Chinese artist Chen Shaoxiong from 2009. “But of course the ads completely disappeared, almost overnight, during the crisis.”

Sigg’s interest in contemporary art started when he was student in Zurich; the first work he bought was a Surrealist painting by a Swiss artist — “It was cheap — I didn’t have any money at that time!” He was more focused on rowing than art, indeed he was a Swiss champion aged 22 and his strongly competitive, high-energy side has been evident since even in his collecting.

After a PhD in law from Zurich university, he went to the Middle East and worked as a journalist until his expertise on the region attracted the Swiss elevator company Schindler. “I actually sold a beautiful escalator with just two gilded steps for the Saudi king’s palace,” he laughs. The company sent him to China in 1977 and Sigg set up one of the first foreign joint ventures there.

During those early years he was closely observed by the authorities, but he says: “I knew there must be another reality than the one I was allowed to see, and I thought contemporary art would help me to see it. But I found out it didn’t exist. There was absolutely no art except socialist realism, and later the first experiments were very derivative of western art.” The change came when Deng Xiaoping opened up the country after 1978. “In visual art, that meant that artists could for the first time make independent works.” Previously artists had waited for commissions rather than risk anything else.

Sigg started collecting Chinese art in the early 1990s. “I immediately realised no one was collecting with this particular focus . . . I gave myself the task of creating a collection that can show the storyline of Chinese contemporary art, from its inception to today.” As a result, “it was definitely not about my taste. I was going about it as I imagined an institution would, and so I had to buy works I might otherwise have rejected.” He grew in prominence as a collector and artists would come to him to ask for advice.

Sigg left Schindler in 1990 and five years later became Swiss ambassador to China, Mongolia and North Korea (until 1998). “I visited North Korea many times and was able to acquire works no one else could buy. Artists were organised into collectives and would produce works on order from the state. The North Koreans wanted me to do the same for their art that I had done for Chinese art. [The authorities] showed me the plan of a museum they would build in Pyongyang for the collection. It was quite wild — they said: ‘You see that door over there, behind it we have assembled the 100 best artists of our country, go in there and tell them what to paint.’ Of course I turned the suggestion down, very politely.”

Nevertheless, Sigg was able to build one of the most important collections of North Korean art outside the country; parts, plus some of his South Korean collection, were displayed in Border Crossings at the Kunstmuseum in Bern, Switzerland, in 2021.

He was able to export his collection from China after his time as ambassador but, he says, that would not be possible in its totality today: “Things changed after the Venice Biennale of 1999,” when so many Chinese artists were featured, “and a few years later a very strict export regime kicked in, directed partly at me: because official China realised there was a whole phenomenon taking place completely outside their control. And that really shocked them.

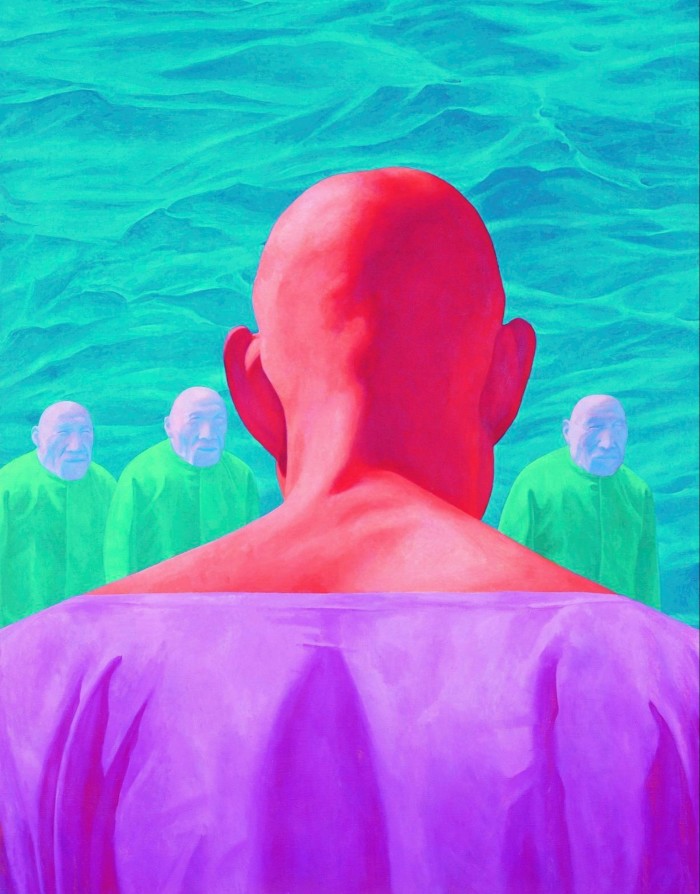

“Under the current leadership, the Chinese want complete control of China, both inside and outside. In my opinion, they have a completely different concept of art in society. They think it is supposed to bring you beauty, harmony and the sublime. But contemporary art is also about opening new spaces for new thought, and that’s adverse to the current thinking. Contemporary art is not your good friend, it’s not your doctor, and at times it’s even your pain.”

In interviews before the donation to M+, Sigg had said he decided to donate to Hong Kong rather than mainland China because the territory was freer. In the light of the current political clampdown, how does he now feel? As we have learnt, works on display have been censored in M+ from Sigg’s donation.

“And yet,” he says, “I would still donate to Hong Kong, and for two reasons. Firstly, it is a great museum. Secondly, of course Tate and other museums wanted me to donate it to them, and they would have given me a great exhibition — then put it in storage. It’s not their core business. Chinese people should have access to their own art, which they don’t know, which is why the collection should be in Hong Kong.”

Is he still collecting? “It’s very difficult to unlearn collecting! Of course, Hong Kong is very interested in the rest of the collection, which rather more reflects my personal taste than the works I initially collected. And the M+ donation stops in 2011 — if I were to donate, it would write the next chapter. But it all depends on the political situation, will it get more intense? I am watching how the situation evolves.”