Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When he entered his sixth decade, Yang Fudong wanted to make a work of art about time and the arc of human life. He initially thought the title should relate to a saying in Chinese, about how you only know your fate when you turn 50, but it was too simple and “not beautiful enough”. So instead he settled on a Chinese character he came across on the first page of an old book, which now means harmony, but he feels might mean water or even city; and on the word for sparrow, a bird of the sea, which might be mispronounced in such a way that it evokes the name of an ancient general.

Yong Que, or Sparrow on the Sea, was shot in Hong Kong in collaboration with Art Basel and the city’s M+ museum of contemporary art, where it is being projected on to the building’s facade and will be visible from across the harbour every night until June. It is the latest work from an artist who trained as an oil painter but became known internationally for the impressionistic techniques of his photography, film and video installations — what he has referred to as “painting with the camera”.

In person in his Shanghai gallery, Yang has a youthful demeanour that evokes the end of the last century, like a skateboarder who has forgotten his skateboard. As with his work, his conversational style does not prioritise straightforward answers or clear-cut storylines. “Sometimes I joke that when you shoot [a film], the story isn’t that strong,” he says. “You paint slowly, and shooting is a bit similar. You shoot slowly, and there’s your life — time is in it.”

Yang, born in 1971, grew up in Beijing and the capital’s accent is still audible in his softly spoken Mandarin. His work often explores the line between reality and falsehood. In a 2010 video commissioned by Prada and shot in Shanghai, actors dressed in clothing from different eras float upwards to the unsettling stop-start sound of string music, though the wires are deliberately left visible. “The things you shoot are fake, but sometimes they are real as well,” he says. The idea of “true or false”, whose characters in Chinese can be simply stated next to one another like yin and yang, is of great interest to him, as are dreams, which are “waiting for you” when you go to sleep at night.

The Hong Kong film, which had to be approved for screening by its Office for Film, Newspaper and Article Administration, revolves around three dancers of various ages. “A few decades go by very quickly,” he says, and the friends around you are changing too: “One might go to England, another to France, another might come back.” Sparrow on the Sea is a black-and-white tapestry of the city’s tropes: trams, suits, suitcases, staircases, mountains, beaches, water, hats, screens, taxis, Buddhas, fishing nets. But Hong Kong, in contrast to convention, here feels sparsely populated, languorous.

The hour-long film required half a month of shooting in the territory, which was “bigger than he imagined it”, despite previous visits. Together with its modern buildings it has “old buildings, old walls and an old texture”; he saw the city as beautiful for the first time. Is there something of the old China in Hong Kong? Yang is reluctant to engage with this. In conversation he is more at ease describing sensation, with its vagueness and paradox. There are sounds that you can hear, he suggests, and those that you cannot, like the sound of a high-rise building. (The film will be shown in the gallery’s cinema with its soundtrack, but the version projected on to the M+ building will be silent against the backdrop of the city.)

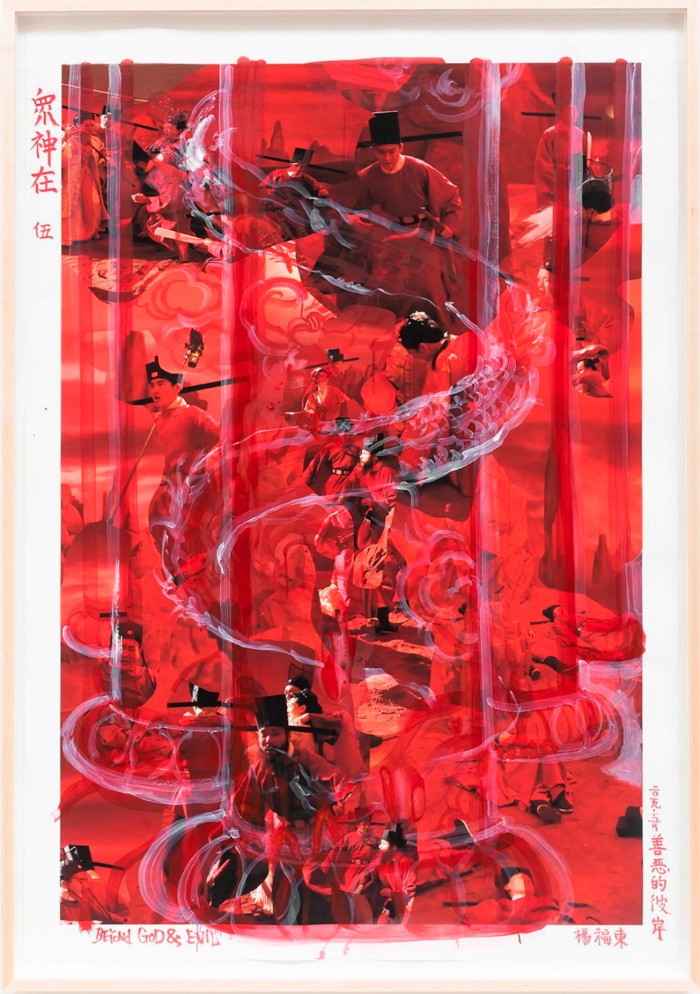

History does percolate through his work, though. He likes Turner, and might call a work about London The Fog of Turner, even if it had nothing to do with him. One piece, Beyond God and Evil, alludes to the similarly titled book by Friedrich Nietzsche. It is part of a project about life in China’s Song dynasty. Is he interested in Chinese history?

“No, I’m actually a very bad student,” he says, adding an expression meaning “just kidding” that he says so often it approaches a verbal tic. In college he was always playing football and basketball, but after graduation, he says, you “slowly find yourself reading books, watching films” and you “start taking Chinese history and ancient culture more seriously”.

There is an expression, sometimes attributed to composer Claude Debussy, that music lies in the spaces between the notes. In Hong Kong, a city full of the jangling of a thousand instruments, Yang’s work is at its most striking in its moments of silence. Its effect leaves the ear straining for sounds that cannot be heard.

Words do eventually arrive. “I’m sorry,” a character says, in one of just three brief moments of Cantonese dialogue in Sparrow on the Sea. “That wasn’t my intention. I just wanted to share this with you. I’m afraid of being misunderstood. As for, as for the future . . . ” The lines trail off, and then, is that a tear rolling down the actor’s cheek? The camera is handled in such a way, ambiguously, that you can’t really be sure.

To June 9, mplus.org.hk