In the middle of Hong Kong’s business district, on the site of a former car park, an unusual new addition to the city’s famous skyline is nearing its opening date.

The Henderson is a 36-storey office building by Zaha Hadid Architects and named for Henderson Land Development, a developer controlled by one of Hong Kong’s big four property dynasties. Its curvy structure is modelled on the city’s symbol, the bauhinia flower’s bud. The cost of acquiring the plot alone was $3bn.

Tenants announced so far include auction house Christie’s, Swiss watchmaker Audemars Piguet and private equity firm Carlyle. “As far as I know, The Henderson seems to only accept tenants of top-notch quality,” says Ricky Tsang, director of corporate ratings at S&P.

But according to three property agents familiar with the project, it currently has tenants for only about 60 per cent of its lettable area. At the 41-storey Cheung Kong Centre II, under construction a block away, agents say occupancy rates were stuck at about 10 per cent in March as negotiations with potential tenants dragged on.

Henderson Land confirmed the current occupancy level but said the project would further “strengthen the group’s foothold in Hong Kong’s central business district and add to [our] recurrent income stream”. CK Asset, the developer behind Cheung Kong Centre II, did not respond to questions about letting.

According to Cushman & Wakefield, prime office rents across Hong Kong have dropped by nearly 40 per cent from their peak in 2019, and government figures show vacancy rates at a record high of 16 per cent. Against this unpromising backdrop C&W predicts roughly 6.7mn sq ft of new office space — 14 times The Henderson’s gross floor area — will be released to the market over the next five years.

The city’s prime office rental market “hasn’t bottomed out”, says Fiona Ngan, head of occupier services at Colliers Hong Kong. “Many multinational companies are downsizing, driven by a weak economy . . . and mainland Chinese companies are not coming in at the [quick pace] as previously expected due to budget limitations.”

It is a similar story in the residential market. Government data shows the number of completed but unsold units has risen 134 per cent from 2018 and prices have fallen about a quarter from their peak in 2021. Last year, the price of the median property in Singapore outstripped that of Hong Kong.

Real estate still matters greatly in Hong Kong. It is how many of the territory’s high-profile business families built their fortunes. The benchmark Hang Seng stock index contains 12 property or construction groups and regular auctions of government-owned land for development raise significant sums for the territory’s administrators.

Hong Kong has seen property market crashes before — residential prices more than halved after the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, for instance. But they have invariably bounced back, often spectacularly so.

Some real estate experts fear things may be different this time around. The notion of “higher for longer” US interest rates — borrowing costs in Hong Kong are linked to these via its currency peg to the dollar — followed three years of tough zero-Covid policies and a crackdown on dissent that has made some international companies and some local residents consider leaving.

“Both residential prices and office rents will find it hard to rally like they [once] did,” predicts UBS analyst Mark Leung.

Hong Kong’s very high population density, challenging topography and economic dynamism have long made it one of the most expensive property markets in the world.

Its most recent real estate boom, driven by low interest rates and growing demand from companies and individuals from mainland China, was also one of its most enduring.

Tycoons’ family members, property agents and economists speak of a “crazy” era in the 2010s where home prices and prime office rents rocketed, buoyed by the city’s strong capital markets and big-spending investors.

Commercial rents in Hong Kong’s Central business district soared to a record high of HK$166 per sq ft per month in late 2018, according to C&W data after a rise of nearly 20 per cent in three years. Residential prices rose by 500 per cent between 2003 and 2021, according to Centaline.

But the correction is gathering pace. Commercial rents are down 37 per cent on average from that peak. “Work-from-home culture has not directly drawn down office rents in Hong Kong,” says Ada Fung, head of advisory and transaction services at CBRE Hong Kong, drawing a contrast with other global business cities. “One of the major reasons was the [weaker] business sentiment.”

By the time Hong Kong’s zero-Covid rules came to an end in December 2022, the US Federal Reserve had already raised interest rates seven times, increasing the cost of borrowing for developers and home buyers alike.

Beijing’s political crackdown has prompted some multinational companies, already looking to cut costs, to reconsider their position in Hong Kong. China’s own economy has also slowed, damping interest from wealthy Chinese individuals and companies in investing in the city.

Ngan, at Colliers, points out that many Chinese companies are no longer doing initial public offerings in Hong Kong, “leading to increasing pressure for relevant professional companies such as legal firms . . . with a number of them downsizing”.

For now, Hong Kong’s CBD office rent is still about 35 per cent higher than Singapore’s Marina Bay, according to UBS. Ngan questions whether a return to previous peaks would be sustainable.

In the residential market, prices fell in each of the 10 months from May 2023 to February 2024. At that point, Hong Kong abolished all extra stamp duties, which at their peak were 30 per cent for non-residents. Prices rose 1 per cent month-on-month in March.

But analysts and agents say interest rates need to come down a lot — or property yields need to rise — for real estate to become attractive for investment again. Gary Ng, a senior economist at Natixis, questions why anyone would buy properties yielding about 3 per cent when “you can get 5 per cent easily” from bank time deposits.

Developers in Hong Kong have been offering discounts of 15 per cent or more for newly built units to clear growing inventories of unsold flats, pressuring the second-hand housing market.

About 140,000 residents left Hong Kong in the two years up to 2022, shrinking the pool of buyers, while wealthy Chinese have been increasingly looking at cities such as Tokyo for “safe haven” property investments as Beijing tightens its grip on Hong Kong.

Home prices are expected to drop up to 5 per cent more this year, according to UBS estimates. Morgan Stanley says that could lead to a “big drop in profits for Hong Kong developers with high exposure to residential inventory”.

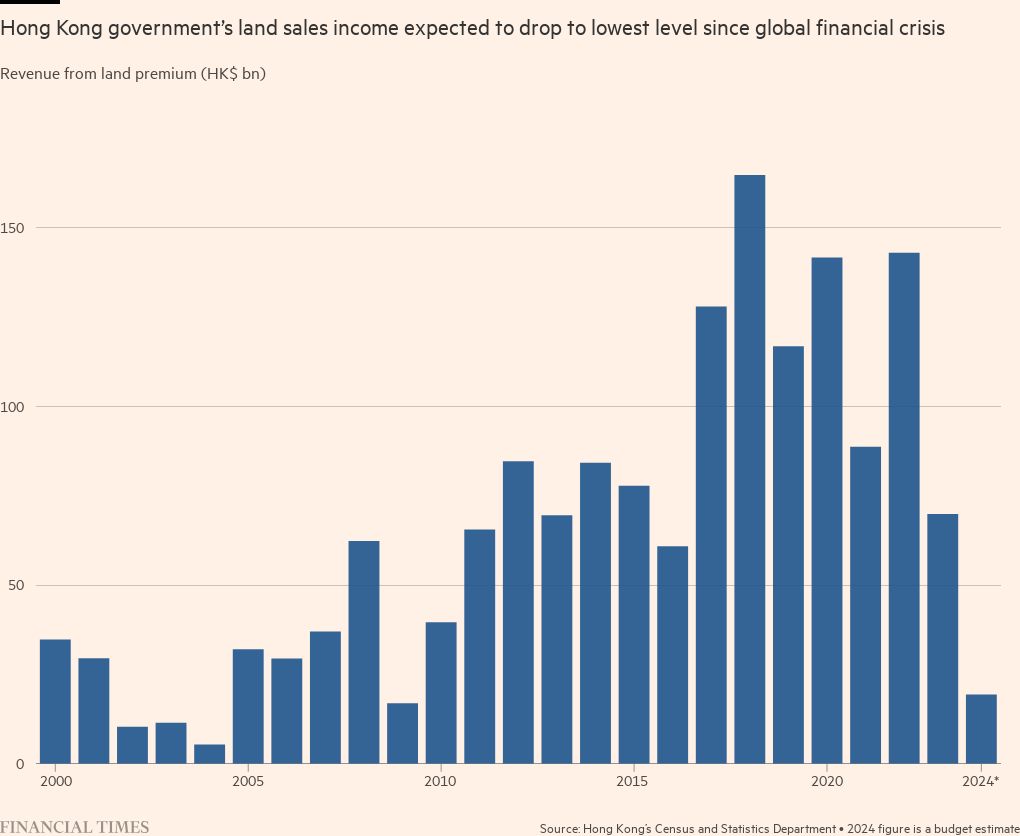

It would also have implications for the territory’s government. Sales of land for development accounted for as much as a fifth of total government revenue in the boom years. But recent auctions have been disappointing — a sign, analysts say, that developers are losing confidence.

The number of failed tenders for residential sites in 2022 and 2023 surpassed the total of the previous seven years, according to JLL, and no tenders were offered for residential or commercial sites in the final quarter of the fiscal year owing to weak demand.

For younger Hongkongers, still living with their parents or crammed into public housing blocks far from the central areas, cheaper housing would be welcome.

The city’s median home price is nearly 19 times its median annual household income according to the most recent data by the Urban Reform Institute — far higher than about five times in Singapore, the UK or the US.

Living conditions have declined as new flats became smaller and prices more unaffordable. Hong Kong’s per capita living space is only about 170 sq ft, according to the latest government data.

As interest rates rose and home prices slid, the number of borrowers in negative equity hit a 20-year high of about 32,000 cases at the end of March.

More than a quarter of Hong Kong’s population lives in public housing, but average waiting times for new applicants are now approaching six years. As the city’s wealth gap widens, many have resorted to renting tiny private subdivided housing units; more than 200,000 people, out of a population of 7.5mn, now live in what have been termed “coffin flats”.

Ken Lui, a 42-year-old Hong Kong investor who made his fortune from residential properties, now owns or manages about 400 apartments split into 1,700 subdivided units. “Hong Kong has not enough housing supply . . . to accommodate every family,” he says. “One apartment divided into three smaller units can accommodate two additional families.”

Monthly rents for subdivided housing were on average about $700 per unit, government data showed, with more than half of these units at a size of between 75 and 140 sq ft.

The Hong Kong government is seeking to expand affordable housing, in line with the drive for “common prosperity” espoused by China’s president, Xi Jinping. Officials at the Liaison Office, Beijing’s official presence in Hong Kong, have also been looking at the city’s property market, according to two people familiar with the matter.

A more hands-on approach in one of the world’s freest economies would likely “strengthen public housing policies . . . while restoring private sector housing confidence and prices”, says Lim Tai Wei, an adjunct senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s East Asian Institute.

Even some members of property tycoons’ own families admit the city’s real estate prices had become unhealthily high. “Hong Kong is so small,” says Poman Lo, an adjunct professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology who is also the granddaughter of Great Eagle Holdings founder Lo Ying-shek and a director of several group companies.

“I don’t think [even] the Hong Kong government wants prices to go back to the old days,” she says.

In the boardrooms of Hong Kong’s big developers — Henderson Land, CK Asset, Sun Hung Kai Properties and New World Development — there is growing unease about the correction.

Their share prices have fallen between 15 and 58 per cent over the past year, against the backdrop of a 9 per cent drop in the city’s benchmark Hang Seng index.

Several spent heavily on land before prices began to fall; aside from the site of its eponymous building, Henderson Land paid a record high of $6.5bn for a waterfront plot in Central in 2021 while rival Sun Hung Kai spent $3.2bn in 2018 for part of the land once occupied by Kai Tak airport, which closed in 1998.

Analysts say returns from these projects could come under pressure as prices and rents come down and developers face higher interest charges on their loans. “This is probably something of a dilemma when a firm chases the market,” says Natixis’s Ng. “The break-even point of the whole project may come a bit later than expected.”

Praveen Choudhary and Jeffrey Mak, equity analysts at Morgan Stanley, estimate that at prevailing prices, developers’ operating profit margins are likely to drop to 19 per cent in 2025 from a peak of about 40 per cent in 2022.

In the short term, developers believe some demand will come back, partly as a result of government policies to attract talented and wealthy individuals, many of them from mainland China, to move to the city.

But the tycoons are less sure how to forecast the market over the next decade or so, analysts say. Future development is likely to be more tilted towards the outer reaches of the New Territories, near the border with China, as Hong Kong’s economy becomes more integrated with that of its vast neighbour.

Projects such as the planned Northern Metropolis and a reclamation project to build artificial islands off the Hong Kong coast for more housing have made some wonder whether long-term demand can absorb the extra supply.

For Victor Li, chair of CK Asset and the eldest son of Hong Kong’s richest man, Li Ka-shing, Hong Kong’s position as a business centre is what will underpin recovery in the property sector and the territory’s economy.

“Hongkongers have had a difficult few years,” he said at the company’s results press conference in March. “What I do think needs to be the case is that Hong Kong must maintain its status as a global financial hub . . . This has not come easily. We must not lose our global standing.”

But many question whether it is necessary for prices to rebound quickly. “I would say, I’m not sure if we are going to still see those [skyrocketing] kinds of transactions,” says Lo. “I don’t think those are very healthy either, because that sends very worrisome signals from the overall society point of view.”

Her preference is for prices to “really slowly get back to a level that is most comfortable for everyone . . . [while] all the biggest business leaders would not be complaining”.

Additional reporting by William Langley in Hong Kong

Data visualisation by Andy Lin