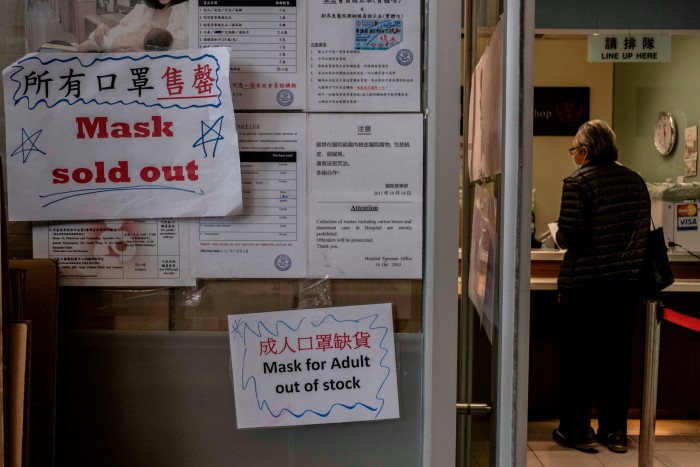

Hong Kong was already a city of masks by the time I arrived, just a week after the lockdown of Wuhan. There were masks on the subway, even if barely anyone was riding it. There were masks in the offices, masks in the lifts, masks in the hotels. There were masks on the late-night ferries across the harbour, masks outside the shops selling masks. If you had come across an elephant wandering up the Peak, you would expect it to be wearing a mask.

The whole world was by then aware of the virus, but few places were quite as aware of it as Hong Kong: the gateway to mainland China, with its own long experience of infectious disease. The masks were just one small part — albeit the most visible — of a rapid community and policy response.

Perhaps that is why, when a government law mandating outdoor and indoor mask use was dropped this month after almost 1,000 days in force, it felt like the end of an era: one of the very final parts of a global effort that also began in east Asia and sought to contain Covid-19 through closure.

Transit, whether for a few days or a few generations, is embedded in the very being of Hong Kong, a place where it is so important to get somewhere else that you can commute to work by escalator. For three years, what was once one of the world’s most open cities became one of its most isolated. Its strict quarantine measures for inbound travellers were not removed until September last year and lingered in watered-down form for months. It was closed off even from mainland China at a time when it was moving closer to it politically; the border only reopened in January, after Beijing abandoned its own zero-Covid policy.

I had been supposed to pass through briefly, but my journalist visa to the mainland was repeatedly delayed for two and a half years. So, as happens to many people in Hong Kong, I ended up staying longer than expected. That layover coincided with a period of both subtle and momentous changes, when the unfolding history was never fully separable from the virus. It raised many questions: about the fading of a British colonial identity after the 1997 handover and a future within, rather than alongside, China — the halfway point in the 50-year “one country, two systems” period passed last summer.

Today, anyone flying in (potentially for free, given that the government has just started handing out half a million free tickets) might wonder how Hong Kong has changed. Is it more like the mainland? And if a chapter of the pandemic has ended, how should we now understand it, and its various sites of enclosure?

The pandemic, at first, made it difficult to ascertain what was and was not normal in Hong Kong. For my first six months, I lived in a hotel. This in itself appeared to be a normal thing to do. But the hotels were not quite themselves.

About the photography

The images in this piece were taken by Lam Yik Fei, an award-winning photographer born and raised in Hong Kong. His most recent book, ‘Chan Nok Kei’, was published in 2021 and shows a decade of tumultuous change in the city. He is currently based in Taiwan.

It was unclear whether the pool was closed because of Covid-19 or, as I was told, because it was winter (average February temperature: 19C). It was hard to say if Christmas songs were playing at the breakfast buffet at Easter because this was traditionally done in Hong Kong, or because, within a collapsing hospitality industry, even the music had become unhinged.

Had I been upgraded to diamond status far earlier than I was entitled to because I was one of the only remaining guests? After a few months we were essentially down to me, a Canadian businessman who was launching a cryptocurrency exchange and a Chinese-Malaysian resident who introduced himself as Nostradamus. I never got to know the staff well enough to discuss these matters properly, maybe because I never saw them without a mask.

Decades after the handover, it’s easy to see the UK everywhere in Hong Kong. Possibly because of the need to counteract the excess of free-flow brunches, everyone in the expat community seemed to be constantly hiking, as though they were conforming to a particular version of middle-class England (the mountains reach a similar height in both places).

Some of the trails, seemingly corroborating this, were named after former British governors. In the botanical gardens, the bandstand was meticulously maintained, and the statue of King George VI appeared more or less intact — unlike the previous statue on that site, which was sent to Japan and melted down during the second world war. Street signs in the vicinity of Queen’s Road, a collection of vaguely recognisable surnames that crop up in other former British colonies, left no doubt as to the territory’s legacy.

Initial caution towards the virus, largely explained in relation to the 2003 Sars outbreak, dealt a blow to the anti-government protests that engulfed the city pre-Covid. But it didn’t eliminate them on its own. In the malls, which you can use to navigate an air-conditioned route through its central district, I once saw a group of young people singing “Glory to Hong Kong”, the protesters’ anthem, against a backdrop of empty designer shops.

Queen’s Road was sometimes still clouded in tear gas, especially around the time of the national security law’s introduction in June 2020, which shifted legislative norms towards mainland China and suppressed anti-government displays both on the streets and in the media. The day after it came in, I went to one of the last protests in Wan Chai. Midway through, a motorbike raced past at an unmeasurable speed, to cheers from the crowd.

About a year later, in the first case tried under the law, its rider, Tong Ying-kit — who had been carrying a flag that said “Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times”, and was also accused of driving into police officers — was sentenced to nine years in prison.

In 2020, the protests were still for a while one of the default topics of conversation, complete with their own dining-room tensions: the contrasting perspectives of the impassioned young, the venerable old and the salaried middle.

I interviewed a priest about the annual Tiananmen Square candlelit vigil in June, which eventually went ahead in Victoria Park in defiance of an ambiguous official ban under Covid protocols (in 2021 and 2022 the park was sealed). At the end of our conversation I checked that he would be happy to be quoted under his own name. “I am very old,” he said with a chuckle, “and not afraid any more.”

When I asked a friend what he thought of the protests, he pointed out that they had been happening frequently since the 1997 handover. Their erasure signalled the long-feared arrival of a system to which people were not acclimatised. One day, I went to a spatially distanced cinema to watch the 2019 French film Les Misérables, about a conflict between police and youths in a Parisian banlieue. The only other viewers were an elderly couple in the corner, with whom I had avoided eye contact because I’d smuggled in popcorn from Marks and Spencer. At the end of the film, I asked them what they thought. “I wonder how much longer we’ll be able to watch films like that,” came the reply.

While the future was viewed with a mixture of fear, anger and pragmatism, the past was comparably absent from discussion. It was not without its protests; when I had lunch with a retired British civil servant at the cricket club, he told me about riots in Kowloon when he arrived in the 1960s. And, when I started to look more closely at the buildings, I realised many of them had a similar architecture. A museum in the New Territories, a bar and restaurant complex in the centre of Hong Kong island, a hotel in the fishing village of Tai O, the University of Chicago’s campus on Hong Kong Island — all, once, had been police stations.

At the height of Covid-era Hong Kong, with most other forms of exercise intermittently outlawed, hiking took on an even greater importance. It was also not the straightforward British cultural import I had assumed. On the last day of 2020, I saw a sign at the top of a mountain that I had previously missed. It was about the Chung Yeung Festival, when it is traditional to climb a mountain. Because so many of its residents came from rural communities on the mainland, the sign explained, “many ancient traditions and customs were brought to Hong Kong and have been unfailingly observed, though with some modifications”.

That was on display on Hollywood Road, where I briefly lived in a serviced apartment in 2021. (I’d had to move because my previous serviced apartment, where you could get a generous discount because of the lack of customers, closed because of the lack of customers.) The road is full of shops selling purportedly Qing dynasty antiques, and on lunar new year the queues for Man Mo Temple stretched late into the night.

In the museums, which opened only sporadically between outbreaks, the signs were rich in Chinese idiom (the Maritime Museum: “It is easy to leave home; what is hard is to return”). The city was an upside-down America where many of the immigrants had left behind, rather than arrived at, a sprawling and limitless continent; where a lost civilisation was still flickering like the last embers of a stick of incense. As with America, it was also full of the practices of other places: Nepal, the Philippines, Australia, France.

The coexistence of the Chinese- and English-speaking worlds in Hong Kong, originally part of an imperial trade bureaucracy, had shifted to an arrangement based around international business. But the city still seemed haunted by often unspoken aspects of its history. Once, I was in a meeting with an investor who told me about the origins of his school, one of the best in Hong Kong. It had been a place for illegitimate mixed-race children, he said, funded by the British fathers they could not meet. When I later looked it up, its origin was listed as an orphanage.

The city’s strict quarantine measures seemed straightforward evidence of its embrace of mainland norms, in order to gain approval from Beijing to reopen the border. But they also brought echoes of the past. The Jao Tsung-I Academy in north Kowloon, formerly a colonial-era “quarantine station” where Chinese labourers would be separated from the general population before travelling overseas, hinted that such practices had also been fine-tuned long ago. The historian John M Carroll notes that, in the 1890s, British measures to counter a bubonic plague outbreak — including quarantine on a hospital ship — were resisted by the Chinese community. The 1904 colonial law that divided the city, preventing ethnic Chinese residents from living on the Peak for decades, was introduced in the aftermath of those outbreaks. Then, too, health policy was inseparably woven into contemporary political divisions.

Like infectious diseases, authoritarianism in Hong Kong has come in many different strains. The zero-Covid strain was mild. Nonetheless, the effects were sometimes surprising. I used to run every Tuesday night along Bowen Road, close to the Peak. At one point, the mask mandate was briefly extended to outdoor jogging, on pain of an approximately $600 fine. Months later, I would sometimes pass other joggers; even if they were not wearing a mask, in the twilight my mind would add one, and as I approached them, I would watch as it dissolved into their features.

Hong Kong is not simply a place where cultures are bound up on top of each other, like layers of geological sediment. It is a place that, once you are truly embedded in it, makes you realise everywhere else is like that. Two years in, I chanced on an exhibition hosted by a local priest who normally lives in Rome. The idea was to paint the Alps in the style of a classical Chinese landscape, which made them look almost exactly like China. “In the beginning was the Word,” he told me, was translated into Chinese as “In the beginning was the Tao.”

The Covid-19 policies were transformative. But Hong Kong had been changing rapidly for a long time. The place I lived in was no longer a city of missionaries, even if, in the basement of the Dr Sun Yat-sen Museum the baptism pool used by the building’s former Mormon owners was faithfully preserved. It was no longer a city where the cricket club was next to the HSBC building. It was no longer a city of a radical media, where in 1871 a Chinese-language newspaper openly criticised a Qing policy. It was no longer, really, a city of newspapers at all — even if people queued up to buy the last-ever copy of Apple Daily. It was not a port in the way it had once been; I passed by the well-known Fenwick Pier before it closed in early 2022, cast adrift in a reclaimed concrete shoreline. Inside, there were videos playing of a time when it was packed with American naval officers. The closing stores were selling CDs at HK$40 ($5) each, three for HK$100.

In his book The Search for Modern China, the late scholar Jonathan Spence notes that, in the 1980s handover discussions between London and Beijing, “the Hong Kong Chinese, lacking representation in the colony’s government, were barely consulted”. At Cantonese-English language exchanges, I met several people who told me they were leaving, but, perhaps unsurprisingly, they betrayed no emotion to a stranger (I asked one young man what he would do in the UK. “Work in a factory,” he shrugged). Others I met there were brought up in English-speaking countries but had come back; one Mancunian used the old pronunciation heon, rather than hai, for the verb “to be located”, as if his native speech were frozen in his parents’ generation.

Affection towards the city was often expressed subtly. The basketball courts were closed for months as part of Covid-19 restrictions, but were routinely swept free of leaves. The oldest trees, their roots slowly tearing up the pavements, were carefully tended, even if they were doomed to be toppled in the next typhoon. One Sunday, I attended a local church opposite an apartment I briefly lived in, even though I had no chance of understanding the service. But just as it began, someone handed me a headset, and an elderly woman in the congregation dashed over to a booth to interpret the sermon off the cuff. Her English was cautiously paced, distinguished, as though transmitted through the wireless.

As may have been true elsewhere, the Covid-19 restrictions sometimes had a way of opening up a place they had closed off. In a two-year window, I only left once for a brief visa trip, and had to quarantine on the way back. It turns out that uninterrupted air conditioning in a confined space numbs your sense of smell. On my midnight release, as I walked down to the harbour, its return was overwhelming: fish and oil.

When the virus finally broke through the barriers and swept the city last year, and most other sports were again temporarily outlawed, I joined a running group where a different volunteer would chalk a trail through the hills each week. One week we were led up a secretive path, at times verging on a sheer drop, that somehow emerged near the top of the Peak, on an old wrought-iron bridge that was that day covered in mist. I’d by then been up the Peak many times and never imagined such a route existed. When I later asked the group leader how she’d found it, she showed me a YouTube guide, in Cantonese, on her phone. It was no secret at all. But the next time I went, I couldn’t find it again.

It is tempting to understand Hong Kong in that way, as a city of vanished moments, a place with its own, almost infectious sense of loss. But just as fundamental is its sense of humour, which every now and then changes the perspective. Just before I left, stopping at a local coffee shop and checking my temperature for the 1,000th time, as the rules for entry mandated, I asked the barista if she had ever in the past few years seen anyone who had exceeded the upper limit. I’ve only seen it once, she said. It had been her, she added: she had been running up the hill.

Thomas Hale is the FT’s Shanghai correspondent

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter